by Ted Ferris – October 2, 2019

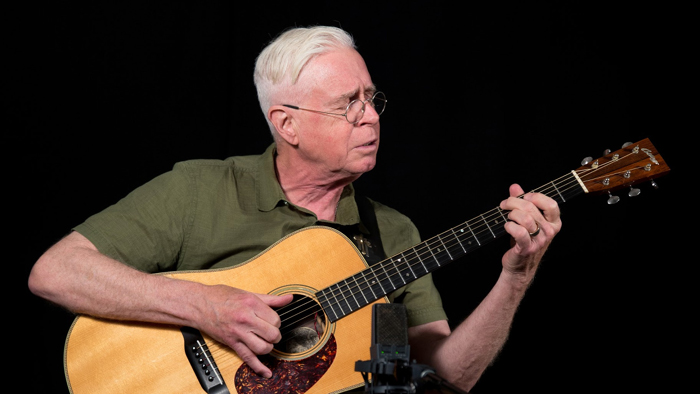

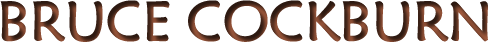

Bruce Cockburn’s 34th studio album, Crowing Ignites, was released on Friday, Sept. 20 on True North Records. The instrumental album contains 11 original songs and was produced, recorded and mixed by Bruce’s long-time confidant, Colin Linden. The album was recorded in a former fire hall located just a few blocks from Bruce’s home in San Francisco.

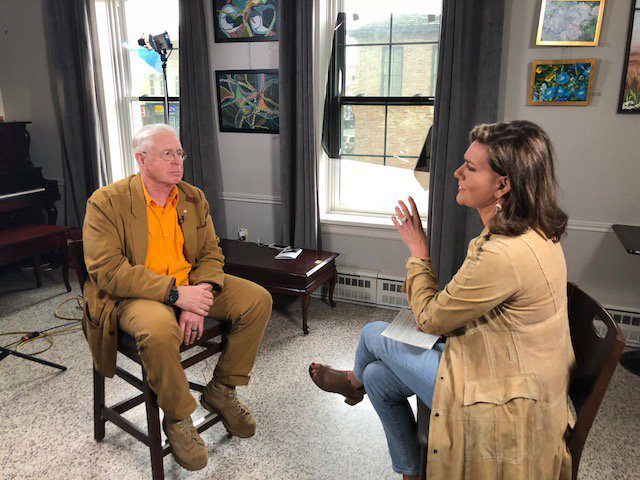

I recently had the privilege of speaking with Bruce about his latest album, the upcoming North American tour, and what comes next for a guitar legend.

Ted: The liner notes explain that the title, Crowing Ignites, was translated from Accendit Cantu, a Latin phrase that appears on the Cockburn family crest. I’m curious to know whether you’ve always been aware of this part of your family history or was this a more recent discovery?

Bruce: Not exactly recent, but it doesn’t go all the way back either. I’ve always been aware of, and always felt kind of connected to, my Scottish ancestry, but I had not ever particularly researched the family history. My Dad did that in the ’70s and ’80s … but I think it was actually my brother who came up with the family coat of arms with that motto on it. It was initially translated as music excites, which I thought was very exciting, and so does he, because what more appropriate (laughs) family motto could I have? But later on I came across other versions of it that weren’t – it was clear that none of these were actually translations. So I actually just went back and translated the Latin, and it came up “crowing ignites,” which I thought had a much better ring to it than the other versions in English. [It’s] just a strong poetic phrase. As far as the ancestry side goes, my Dad actually put it together in a kind of self-published book. He’s the one that did that work; not me. But the connection to Scotland has always been there and remains. It was in the ’90s when we discovered that motto, but the translation was only this year … I was looking at that Latin phrase and thinking … “It doesn’t say ‘music excites,’ and it doesn’t say ‘he arouses by crowing,’ and it doesn’t say a couple other things that people claimed it said. So I got excited and went after it and translated it. And then when I discovered what it really said, I got much more excited … Then my wife said, “You gotta use that for your album title.” So I did.

Ted: Was the concept for Crowing Ignites being an instrumental album in place before the selection of the album title?

Bruce: Oh yeah. It’s not a concept album other than the fact that it’s all instrumental, and that was the intention to do that. Instrumental music, for me at least, isn’t really about anything in particular. It’s about itself … It exists, and it has the capacity to touch you in whatever way it does, and that’s it. … Pieces get titles because you have to call them something, and sometimes you get lucky and think of a title that really fits the piece. Sometimes the titles are obvious right away, and other times you have to struggle with it for a while. But in terms of the album as a whole, the plan was to initially to make a Speechless Two. We were going to collect the various previously released instrumental pieces that weren’t on Speechless and then add some new pieces to that and basically do the same thing we’d previously done ’cause there seemed to be some interest on people’s part on having that, and it appealed to me. But then I started writing pieces, and they just kept coming. So it became Crowing Ignites instead of Speechless Two.

Ted: You recorded the album in a former fire hall in San Francisco. Did you encounter any challenges converting the space into a functioning recording studio? From the photos that I’ve seen online, it looked like there were several hard surfaces you may have had to contend with.

Bruce: No, actually, far from it. It was the easiest thing. Kind of the most hassle-free recording I think I’ve ever done. … The room sounds great as it is. It’s true when you look at pictures you see a cement wall, but the cement wall is very heavily textured so it doesn’t reflect the sound … at all. And there’s a lot of wood in the room, so it really sounded nice. I had heard music in there before, and so I knew that it sounded like it did, and it just seemed like the combination of that and its proximity to where I live and my daughter’s school and so on it made it very convenient. My friend, who owned the place, was very happy to let us use it. Colin … went out and rounded up the gear and brought it in and set it up. It didn’t take much. It came in suitcases and it set up on a table, and there it was. I brought in all my stuff that you can see in the pictures: chimes and Tibetan singing bowls and all sorts of things with strings on them, and then we just – we spent a great week making a record.

Ted: While it sounds like the studio came together quite well, did any particular song present any unique challenges? I understand that “Seven Daggers” and “Bells Of Gethsemane” were constructed in the studio, and you used a vast assortment of unique instruments on each song. Did you have any difficulty putting them together, micing and recording them?

Bruce: Well, … not beyond what you’d expect. Let’s put it that way. I mean, everything’s a challenge. You’ve got to get it right, but there [were] no real difficulties at all. The most complicated one is “Seven Daggers.” We constructed that one and “Bells of Gethsemane,” as you pointed out … in the studio. All the other pieces, I knew what I was going to do when I went into the studio. But with those pieces, all I knew was that I had an idea for certain kinds of layering that I wanted to do. In the case of “Seven Daggers,” I wanted to use little kalimba things that I have, and the charango. … The charango can be tuned so it will play in A minor with the kalimbas. So we created loops out of those and made a layer out of that and then just started adding things to it. [Then] Colin put on the baritone guitar part, and I played the 12-string over top. That was the most elaborate of the constructions. “Bells of Gethsemane,” I just put down a layer of singing bowls and then another layer of singing bowls and then a layer of chimes and some other stuff and just played over top, playing the baritone myself on that one. So I wouldn’t call them challenging. There’s a process, but the only real challenging part, which is always there, is to get past the conditions of the day … How tired are you? Or how imaginative do you feel at this moment? … Those kinds of things. But that’s always there.

Ted: I recognized a few of the musicians that perform on Crowing Ignites. However, one name that I didn’t recognize was Bo Carper’s. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about him.

Bruce: Bo Carper is a guitar player that I’m acquainted with here in San Francisco – a very good guitar player actually. We met at a social gathering, and we ended up jamming together, so that’s how I found out what kind of guitar player he is. Because I don’t really know many people in the music scene here, I [contacted] him and asked him if he knew any percussionists, because I was interested in having somebody play percussion on some of the pieces. He gave me a couple of names. … One I didn’t get a hold of, and the other one … was already booked for the time period that we needed him for. So that didn’t pan out … I let Bo know that, and he said, “Well you know I’m a really great shaker player.” I had never heard anyone say that about themselves before, so I immediately perked up. And so he came in and played shaker. I thought this will be fun to try, or whatever. It’s not what I was exactly looking for, but it might work really well. And I think it does, and I think he did a fantastic job. A couple of the pieces we played live together, and then a couple of them he did as overdubs. Colin was involved in every aspect of the album, and he plays on the aforementioned “Seven Daggers” and also on “Blind Willie,” putting a great slide guitar part on that. And then Janice Powers, Colin’s wife, plays keyboards, as she’s done a lot of times before for me on other albums. She’s really great at coming up with these atmospheric keyboard kind of landscapy parts that I think contributed greatly to the overall effect of things.

Ted: Another person listed on one of the tracks is your daughter, Iona. What was it like including her in the recording of the album?

Bruce: It was fun. She got to clap along, and she was excited to be able to go in studio and clap her hands. I don’t know if it’ll mean too much to her in the long run, but it was fun at the time.

Continue Reading…