Singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn talks about Christianity and what he’s dropping from his setlist

by Bill Forman May 11, 2022

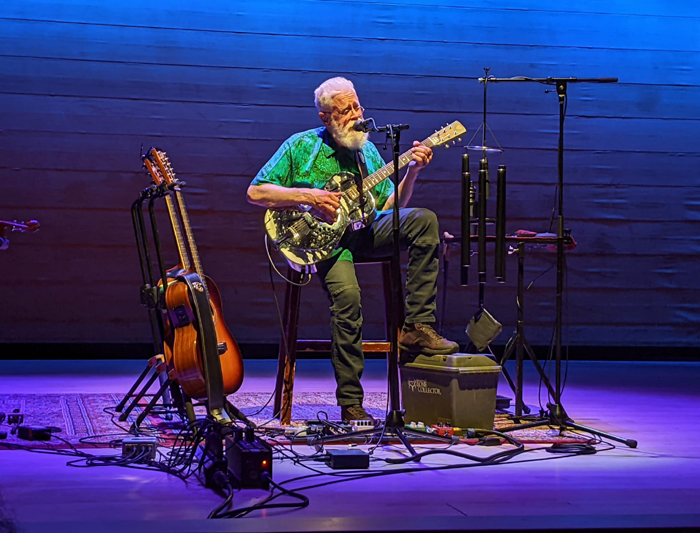

When it comes to live shows, Bruce Cockburn has no shortage of songs to draw upon. There are the ‘80s hits like “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” and “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” the steady stream of albums that have followed in their wake (which have earned him ten Juno Awards in his native Canada), and a few unreleased songs he’ll be debuting on his current tour.

But one hit that Cockburn won’t be playing is “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” a song he wrote after visiting Guatemalan refugee camps back in 1984. It was Cockburn’s best-known hit in America, as well as his most controversial, with an accompanying video that depicted the genocide carried out against Indian villagers by the Guatemalan army, with whom the CIA happened to have close ties.

While MTV aired the music video frequently, radio programmers were less inclined to add the single to their playlists, not least because of its closing line: “If I had a rocket launcher, some son of a bitch would die.”

The song has long been a staple of Cockburn’s live shows, but that changed back in March when Russia fired more than 30 cruise missiles at a Ukrainian military base.

“I’d been playing it on all the U.S. dates, but stopped during the Canadian shows, because I just felt like it’s gone too far that way,” says Cockburn. “It’s always made me uncomfortable when people cheer for that song. And I don’t mean applause at the end of it because it was a good performance or something. But just when I sing the various lines — like even at the end of the first verse, ‘If I have a rocket launcher, I’d make somebody pay’ — and there’s invariably somebody — some male — in the audience that hollers out, ‘YEAAHHH!’ And I hate that, because that’s not what it’s about. And if they were thinking about what they were hearing, they would not do that. And I just didn’t want to play into that kind of sentiment in the current situation.”

I think my relationship with God is the most important thing in my life.

— Bruce Cockburn

This isn’t the first time that Cockburn felt the need to give the song a rest. “The same thing happened after 9/11,” he says. “I didn’t sing it for a long time after that, because, you know, people were just looking for motivation to go out and do really bad things. Not that anybody in my immediate audience is likely to go do that, but it just was playing into the wrong part of the heart.”

While Cockburn has written numerous songs about human rights violations and third-world exploitation, he’s always done so with a poetic sensibility, and a depth of emotion, that sets him apart from more didactic political songwriters. He’s also a phenomenal guitarist, which is particularly evident on a pair of instrumental albums that prompted Acoustic Guitar magazine to place him on the same level as Django Reinhardt, Bill Frisell, and Mississippi John Hurt.

“When I was learning to fingerpick, I did my best to emulate Mississippi John Hurt and Mance Lipscomb, and some other guys like that,” says Cockburn. “Brownie McGhee was also an influence. I saw Brownie and Sonny [Terry] play dozens of times at this club in Ottawa that I hung out at on a regular basis. Well, probably it wasn’t dozens of times, but it might have been, because they’d come a couple of times a year. I love that music, and it’s still part of what I do.”

Cockburn was 14 years old when he found the dusty old guitar in his grandmother’s attic that would put him on the path to a life in music. Another pivotal moment, he says, was dropping out of Berklee College of Music.

“I was headed toward a bachelor’s degree in music, which would have entitled me to teach music in high schools, which I had no interest whatsoever in doing,” he says. “I was interested in the content of what was being taught, but not in terms of using it as a teaching career. And then I reached the point where I had this realization, ‘I gotta get out of here, this is not where I’m supposed to be.’ And I listened to that, and I acted on it.”

The other primary influence on Cockburn’s life has been his spiritual beliefs, which find their way into his lyrics without hitting you over the head with them.

“I think my relationship with God is the most important thing in my life, and the one I sort of struggle with the most probably too,” he says. “I wasn’t plugged into a community for a very long time, but through a combination of circumstances in San Francisco, I started going to church again after having not done it for maybe 30 years, 40 years. It was a small, non-denominational church with all these really accepting and loving people. The congregation was racially mixed — you know, people from all sorts of Asian extraction, African-Americans, white Texans, and Samoans — all kinds of different cultures mixed there. And it was accepting of gays and, you know, whatever else — people that feel, as I do, that their relationship with God is of paramount importance.

“When I showed up, they didn’t know who I was. I was just the old guy with an attractive wife, who’d discovered the church before I did, and eventually persuaded me to go. Then they found out I played guitar, and I ended up sitting in with the band and becoming more or less their guitarist. But then COVID, of course, killed that. So new things have happened since, but there was definitely a sense of community.”

All of which is a far cry from the divisive preachings — or, as Cockburn puts it, the vile bullshit — that comes out of the religious right.

“If you start using the Christian faith as a reason to hate people, it’s completely antithetical to what it’s about,” he says. ”And yet, historically, of course, it has been used for that over and over again.

“But, you know, I don’t think anybody who pays attention to what I have to say is gonna confuse me with that other stuff. The challenge, of course, is will they listen to what I have to say, or just write me off? Either way, I’m not gonna stop calling myself a Christian. And if you can’t deal with it, well, that’s your problem.”

Credit: Colorado Springs Indy