BY COURTNEY DOWDALL

May 2, 2024

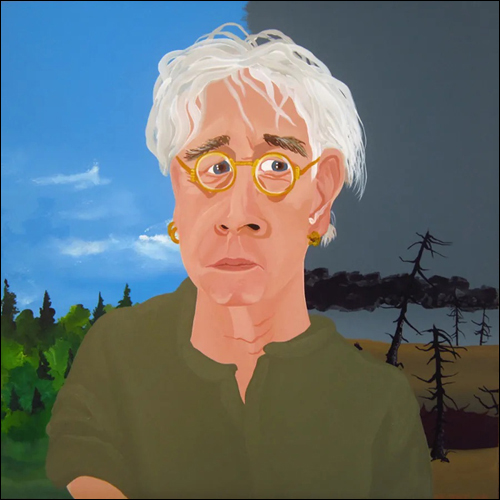

Photo of Bruce Cockburn by Daniel Keebler

Bruce Cockburn is a Canadian guitar player, songwriter, and activist who has traveled the world as a “musical correspondent” to document tragedies and triumphs of the human spirit. With a list of accolades and awards about a mile long, he is renowned and respected for his “cinematic” style of songwriting. He has released more than 35 albums over the course of his career spanning 50+ years.

The last time Bruce Cockburn came to St. Louis in October 2018, he sold out the joint. In the intervening years, he’s added two more original albums to his catalog, including his most recent work, O Sun O Moon, released in 2023, in which he continues sharing observations of the human experience: relationships, spirituality, politics, and wonder. He returns to Delmar Hall on May 7.

We had the honor of speaking with Bruce Cockburn from his Canadian home as he returned from the European leg of his 2024 international tour.

The Arts STL: Well, I’m so glad to have this opportunity. I was introduced to your music a very long time ago by my then-boyfriend, who’s now my husband. We were like 13 at the time, and he made me a mixtape that included a lot of music he got from his father. Songs like “Hoop Dancer” and “Rose Above the Sky” and “Tokyo” were some of the first songs of yours that I got introduced to, by my husband’s little 13-year-old poetic soul, which just melted my heart and has been with me ever since. So to have this opportunity was something I absolutely could not pass up. Thank you so much for making the time! Thanks for continuing to make all this amazing music over the years! And thanks for coming to St. Louis next month.

Bruce Cockburn: Yeah, I’m looking forward to it. And you guys were ahead of the curve in the US. With those particular albums and songs and whatnot. Things were just starting to get rolling in the US at that point.

Can I ask, are those songs that I could ever anticipate hearing on tour?

BC: Actually, “The Rose Above the Sky” I have actually done a little bit lately. Not in every show. It’s one that, for me, I always have the dilemma, when I’m planning a show, knowing that there’s only so many long, slow songs you can put in. You know, you gotta have some energy in the show, too. So, that one kind of just got ignored for a long time, and I didn’t think about it too much. Then, when people started asking for it, and [it] came up in conversation so many times recently, that I started learning to do it again.

How does it feel to revisit those songs you haven’t played or had those words coming out of your mouth in so many years?

BC: It kind of varies. On the one hand, it’s interesting to revisit the songs like, ‘Does it still mean the same thing? What did I mean by that?’ A song like that—all the songs, really, take me back to where I was when I wrote them. Kind of like looking at a photo album of old photographs. So, I have mixed feelings about it generally. Because it’s a song that has pain in it. That’s there. It’s also fun to kind of go back and figure out how to do the damn thing. There’s a lot of guitar parts I don’t think I’d be able to figure out, having forgotten what they were. I guess, given enough time, I might be able to, but some of them were fairly complicated. That one wasn’t too bad, but some of them are quite challenging.

Would you ever consider having a pinch guitar player? We recently saw Elvis Costello and there were a couple of times where he said, “You know what, I want to play this song, we’ve got the full band, so I’m gonna let somebody else take over the guitar work on this, because it’s just not as familiar to me anymore.”

BC: No, I’ve never done that. I have occasionally reworked guitar parts. There were songs, some of the stuff from the mid-‘80s, where the bands were big and the guitar parts were shrunken, to accommodate all the different instruments—to figure out solo versions of those songs. A song like “See How I Miss You” or “World of Wonders,” those I had to invent new guitar parts for, because the original ones were designed to be part of a big band.

In other cases more recently, because I’ve got arthritic hands, I’ve had to rework the guitar parts in some quite familiar songs that I have played a lot, just because it’s become too difficult to play them properly. I mean, I can kind of hack my way through “Pacing the Cage,” for instance. I’ve just now relearned that, or reworked it, rather. Because I hadn’t forgotten the song, but the original way of playing it was not available to me anymore. There’s a few songs like that, that I’ve had to rework. And that’s also fun, actually, because it’s kind of a challenging exercise: how do I get the same feel and keep the same relationship between the guitar and the melody, and do it a different way?

What are the important pieces to keep? What is essential?

BC: Exactly. The guitar parts are essentially, except for some of those ones in the ‘80s, they’re basically compositions that are designed to go with those lyrics and that melody. It’s not quite like writing a whole song to come up with a different guitar part, but it’s a little bit in that direction. Trying to keep the same sense of what the composition is, and play it a different way, can be a little tricky. But that said, it’s been working with a few songs that I’ve had to do that with. Most of the stuff is not a problem because, you know, they do what I want them to do. But with some it has presented that issue.

What has been your response or your reaction to cover songs? Or other versions? Does it feel like they capture the same pieces that are important to you? Or maybe pick up on a different piece that wasn’t your emphasis but was more critical in their interpretation?

BC: Yeah, once in a while, it seems like somebody actually got the song. Most of the time, it doesn’t really seem like that to me. I mean, I respect the fact that everybody is going to do their own take on the songs. That’s what they should do. But sometimes it feels to me like they didn’t really understand what it was that they were doing, what the song was.

Other times, it works great. When Jimmy Buffett died, my wife started playing a whole bunch of Jimmy Buffett stuff, including five songs of mine that he did. And there’s a duet with Nancy Griffith of a song called “Someone I Used to Love,” another slow song, that I do too many of in a show. They did a beautiful version of it that really captures exactly what it should be. And yet, it’s clearly them doing it. Judy Collins did “Pacing the Cage,” and that worked great. Other people… sometimes… you know, it might be an age thing, maybe I’m not sure. I just thought of this, because the two examples I gave are both mature people looking at songs from a perspective of having had a life. And some of the younger artists that record the songs, I’m not sure that they actually know what they’re about. But that’s a sweeping generalization. And it’s probably unfair to a whole lot of people. There are many, many recordings of my songs that I haven’t heard, too. So, nobody should think I’m picking on them in particular.

That must be exciting to hear so many different versions and perspectives reflected back to you.

BC: There was a Toronto guitar player, Michael Occhipinti, [who] recorded a whole album of my stuff, and it was completely deconstructed and made into jazz, and it’s really good. And it was really interesting to hear that take. There’s no lyrics, it’s just the music, but the version of “Where the Lions Are” is pretty amazing. And who would have guessed that you could take it in that direction? Certainly not me. So, there’s that side of it, too. It’s not a question of how much they mess with the song. Unless they don’t mess with it in a respectful way, or, rather, unless they mess with it in a way that isn’t respectful, or it just doesn’t sound like it gets it.

I’m gonna have to look for that. That sounds amazing. Do you have any role models or any folks that you’ve looked to for the way they’ve advanced their career or approached their music over time? Like, “That’s the way to do it. They did it right. That’s how I want to do it.”

BC: No, I don’t think of it that way. There’s been many people who’ve influenced what I do over the years, dozens at least, but some major ones back when I was getting started and just trying to understand what music was all about… There were guitar players: Wes Montgomery and Gabor Szabó. There were old blues guys: Mississippi John Hurt, Mance Lipscomb, Brownie McGhee. There was Bob Dylan and other songwriters in the ‘60s. That was an era when a lot of us got beyond the limitations of pop music in terms of our understanding of what you can do with a song. Dylan in particular, but others too, who were exemplary. Gordon Lightfoot would be another one. People who were writing beautiful songs that were more than ‘baby I want to …’ There’s nothing wrong with that kind of song, but it’s –

It’s a different kind of song.

BC: I mean, I cut my teeth on Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, And that’s pretty much all they play, pretty much all they were saying, was, you know, getting or trying to get laid or wishing they were getting laid. That was fine. It was exciting as a 12- and 13-year-old. But the discovery that you can write songs that actually said stuff was eye opening. Some of my friends, when I connected to the folk world, in my latter teens, I hooked up with people who have been aware of this kind of stuff all along, they’ve listened to Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and all these people I had never heard. So for me, hearing and discovering those kinds of songs, but then right away, along came Bob Dylan—I didn’t think of myself as a songwriter, I just related to it really well. At the time, I was just a guitar player. And that’s all I aspired to be. I went to music school to learn jazz composition, to write music for big bands. That’s what I thought I was going to be doing. And then I got seduced by songwriting and went that way.

I read this quote of yours somewhere: “My job is to try and trap the spirit of things in the scratches of pen on paper.” Is that your transition from just the instrumental piece to capturing the words as well as the music?

BC: Very much so. I didn’t understand what I was doing, at first. I thought, “I’m listening to these people that are writing these great songs, maybe I can do it, too.” And the first song I remember writing was very derivative of early Lightfoot. Fingerpicking, nature imagery, and I don’t even remember any details of it now, but that’s what it was then. And then I was heavily influenced by blues and listened to a lot of blues. Not so much Chicago stuff, but the old country stuff, and jug band music and all that. Those were the roots.

And rock and roll. I was playing in rock and roll bands as I was doing gigs in the folk scene, solo or with friends. With hindsight, the second half of the ‘60s was all about learning how to write songs. And I wrote a lot of songs that I pray no one will ever hear during that period. But by the end of it, I had a body of stuff that I thought was worthwhile. And I liked it better when I played those songs myself than when I played them with any of the bands I’d been in. So, that that’s what went into my first album and half of the second one.

So, speaking of the blues, I just stumbled upon this video of you meeting Ali Farka Touré. What an amazing experience that must have been. I know travel is very important to you and your music. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about travel and why it’s so important for, for that job, to track the spirit of things? Or for just being a human in general?

BC: Well, I’m not sure travel is required. But it’s been part of my life just because I like doing it, and because I’ve been given the opportunity for interesting kinds of travel on many occasions now.

The trip to Mali wasn’t about songwriting; it was about desertification and making a TV documentary about that, and how that particular group of people there were dealing with it. But because I play music, and because I have listened to some music from there, we thought it’d be cool in the process of the film, if they tried to put me together with some Mali musicians. Toumani Diabaté, the duet I do with him is better than the thing with Ali Farka Touré. It came out really, really well. But the Ali Farka Touré thing was just happenstance. We went to Timbuktu, and we were planning to stay overnight. We were on our way to our ultimate destination, further southwest of there, but we thought we’d go through Timbuktu and see it because we’re so close. So we had a hotel there, and the hotels are not like staying at a Holiday Inn. There were a whole bunch of Americans there. Two guys had this radio show called Afro Pop—I don’t know how popular it was, but it was syndicated. I don’t know if it was on NPR, but it was that kind of show, where they just looked at music from all over Africa. And they had organized the tour. So, there was like a dozen Americans, also at this hotel, and Ali Farka Touré was going to play for them that night.

I had met him at a festival in Canada, some years before, which he reminded me of, actually. I knew about him, but I didn’t remember that I’d actually met anybody. “Oh, Bruce!” and he shows up wearing a purple three-piece suit and a purple Fedora, which is like—you don’t dress like that Timbuktu. You could, you can, and of course he does. But everybody else is looking pretty poor and traditional with turbans and robes and whatever, so there he is doing this. And he invited me to sit in with him. That’s what you saw. It was fun. That whole trip was super interesting. But also, if you’re gonna look for the video of that, the film was called, River of Sand, I think you can get to it from my website. It’s got that in it, and the duet with Toumani Diabaté, and an older guy whose name escapes me at the moment, an older guy that played an instrument called an ngoni, a precursor to the banjo. That’s pretty cool, too. So there’s that music and then the film itself is—if you’re interested in the topic, it’s interesting.

Absolutely. So, it was the issue that drove the trip, and this was kind of serendipitous.

BC: That’s been the case with most of the more exotic travels that I’ve taken. It’s never been about going looking for songs. It’s always been about what people are doing in certain kinds of situations. In Nepal, the two trips in Nepal were under the auspices of a Canadian NGO that does development work there. And the two trips in Mozambique—one was about feeding people displaced by the civil war that was going on, and the other was about the landmine issue after the war was over. People can’t go back to farming because there’s landmines all over the place.

I’ve done lots of traveling just for my own amusement, too, but that’s more like being a tourist and less likely to produce the interesting song content than some of these other trips.

Do you feel like those travels influence your sound as well as your ideas and your activism?

BC: I think the Mali trip did. There’s a couple of songs that relate to that on Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu. In some of the songs on that you can hear a little bit of that West African influence in the guitar playing. Maybe, or I imagine it’s there, it is certainly there in the lyrics to the song. Central America didn’t really influence me much musically. They have great music there, and the same with Mozambique. That had less effect on me than the stuff I was seeing apart from music.

No marimba solos after your Guatemala visits?

No, I mean, I like marimba. There’s no video of it, but I did jam with a band of some Guatemalan refugees, in the same setting in which “Rocket Launcher” came from. These refugees had carried the marimba from their village when they fled what they fled from, which was horrendous stuff. Everybody carried a piece of it, and they put it back together when they could settle in this makeshift refugee camp. And because we showed up with guitars, they pulled out the marimba. These guys put on their good shirts.

And, the way they play, two to three people play the same instrument. One guy plays bass parts. One guy plays chords. And the other guy plays the melody. It’s like having a giant piano with three people playing it. It was really interesting. And little kids all danced around. It was very poignant actually, because the situation they were in was horrible. But they were partying when they had a chance.

That says so much, that that was a priority in that horrible journey. That was a priority, to bring that instrument.

BC: I was amazed by that. It says something really good about those people, the degree to which they had their crap together. They were organized. They had absolutely no food, they had no prospects, but they were keeping their organization together and keeping the families together and maintaining their dignity. It was kind of heartbreaking.

I imagine you’ve probably seen a lot of heartbreaking things in the places you’ve been and the issues you’ve dug into and tried to be supportive of, or tried to be part of bringing light to those issues. Do you consider yourself an optimist? An idealist? How do you do that?

BC: [laughs] I don’t think in very optimistic terms, but I can’t shake the feeling that things are alright. I’m not in Ukraine right now. I’ve never been a victim of those things myself. I’ve been up close with some victims, and I certainly heard terrible stories from those people. And of course, you don’t have to look hard to find terrible stories in the news. But I just can’t shake the feeling that something’s going to be alright. But it doesn’t stand up to rational scrutiny because when you look around, it just feels like everything’s going straight down the tubes.

You know there are some bittersweet comments on your new album as well. I’m going to read you another quote I found—“Part of the job of being human is just to try to spread the light, at whatever level you can do it.” You still seem to be effective at spreading that light despite it all.

BC: Well, that’s not my light. It’s the light that I receive. I think the point of being alive is to spread it, so I’m grateful when a song is given to me that does that. In a way, it’s an ongoing theme for me. It didn’t start out as a conscious thing, but it’s what seemed like it was worth writing songs about. Even when the songs are expressions of my own or someone else’s pain, it’s all in the context. The worst example of that would be “You’ve Never Seen Everything,” where the whole song is a catalog of completely horrible things, and the chorus is going, ‘Even though if you’re looking at all this stuff, you haven’t seen everything. There’s good stuff, too. The light is there too.’ I probably won’t write too many songs that go that far in that direction. But it’s there. It’s what life is all about, so it should be in the song.

Did you say ‘when the song is ‘given to me’?

BC: Yeah. I don’t go looking for them. I try to maintain an attitude of receptivity, but the ideas come when they come, and I feel like they’re gifts. Intention goes into it once there’s an idea, once something starts to feel like it’s going to be a song, then I work on it consciously. But otherwise, it’s a matter of waiting for that gift.

Do you feel like you need to train yourself to come from a place of positivity with all these things that you’ve seen and experienced?

BC: Well when I went to Iraq, for instance, I went hoping I would get a song. I didn’t. I did end up with a song, but it’s a little forced. It wasn’t as much of a gift as it was me pushing the issue, too, because I really wanted to have a song about being in Baghdad. There’s been a few other occasions where I’ve done that. It never works as well as when I just wait for it and let it happen. I’m not sure I would have got a song if I hadn’t pushed it, and so, whatever, it all comes out in the wash.

But with the trip to Afghanistan, I didn’t expect to get the song out of that, but I did. “Each One Lost” came out of that trip, and that was a gift, totally. It was a painful one, because the occasion that inspired it was a sad occasion. But the gift was there, regardless of that. And it isn’t always fun. I mean, “Rocket Launcher” was not fun. It wasn’t fun to write, it wasn’t fun to hear the stories or be in the situation that set it up. It’s never fun to sing it. But it seems necessary. If you’re a journalist, you’re someplace close to report on a situation, and you’re not going to just report on the things that feel good. You’re going to report on what you see. And for me that’s the same thing.

Does it take effort to find that place of love to anchor those things in? It seems like that would be a challenge in those situations.

BC: Sometimes it is. I think as time has gone on, it’s become less difficult. Central America was the first time I’d been in a war zone, and it was… it was pretty shocking. I didn’t see action or anything like that. I didn’t stumble over dead bodies or whatever, but I was among people who did do that. In an atmosphere where violence could unfold anytime, the feelings run pretty intensely in situations like that. All kinds of feelings—the good ones, too. Because love really comes to the surface in a situation where all the people you’re sitting with may or may not be alive tomorrow. I mean, that could be true anytime, anywhere. We don’t know who’s gonna die when. But in a war zone, that’s really front and center.

There’s this sense of kind of … camaraderie is not quite the right word, but it’s something like that. That’s too light a word. But there’s a sense of shared experience people are willing to extend to each other. In those situations, of course, those aren’t the people that are about to shoot anybody. That can be negative, too, because that same sense of us as a group can be directed in a hostile way towards someone else. Sitting in Managua, the war wasn’t right there—the war was off in the countryside—but there was just this warmth that was readily available, because the big concerns were the appropriate ones: life and death, and how we get along. People were thinking less about their—this is supposition, I didn’t ask anybody what they were thinking about—but it seemed as if people were thinking less about their immediate concerns and more about the fact that we’re all alive in the same place at the same time. At the time, I remember thinking, ‘This is how journalists get to be war junkies.’ Because it’s exciting. This warmth, this ease of forming—not deep friendships, because you don’t know these people. But the sense of being chummy with people and everybody accepts whatever—it’s an attractive feeling that it could be addictive if you did enough of it.

Sure. Well, and that fragility is really apparent in those situations. Aside from being a war junkie, how do you keep that feeling with you, when you’re not in those situations of imminent danger?

BC: That’s a good question. For clarity, I don’t think I’m a war junkie, although I certainly I had those experiences.

But I’m sure they’re out there.

BC: There’s an attraction to that stuff, but it’s also tempered by fear. Am I going to go into a situation where I’m actually gonna get shot at? I prefer not to do that. It was always a possibility, but a fairly remote one, in the circumstances in which I’ve done that kind of travel. Maybe not remote, but lower on the scale of probability. I wouldn’t seek out that situation particularly, unless there was some real compelling reason. But something just inherently risky and that’s all it is? I’m not that kind of person. I’m not an adrenaline junkie like that.

But how do I maintain that? Over time? Again, if you experience that enough, and you live through enough stuff … I guess it matters that I’ve held that in front of me as a desirable part of life like that. If you don’t think about it, maybe it doesn’t work the same way. I don’t feel like I have goals, but I recognize that there’s a way to live and a way not to live. Practicing that over time eventually gets you to a place where you can be more open to that kind of stuff. That doesn’t rule out the ability to get angry at things that make us angry. But the anger is less inclined to take over than it might have been when I was younger.

That is one of the gifts of time and perspective, isn’t it? So along those lines, thinking of one of the more recent songs “To Keep the World We Know,” I was curious: what about the world we know do we want to keep and what do we want to let go? What do we have to let go? Do we want to keep the world we know?

BC: [laughs] The point of phrasing it that way is that, we’re confronted with more than a possibility of finding ourselves in a world we don’t recognize. And what are you gonna do with that? And not in a good way. It’s not like we’re suddenly going to find ourselves going through the pearly gates and walking on the streets of gold. What do we do with that? It’s going to be that life has become extremely difficult for most of us. And then what? So? That’s what I’m thinking in that song. There’s lots about the status quo that is not worth keeping, but it’s hard to know how to get rid of that without getting rid of the good stuff, too. So, with the complicated prey-slash-predator creatures that we are, it’s hard to step away from that.

Sometimes this is a good thing and maybe sometimes it’s not—separating the art from the artist, trying to separate the musician from their life or their politics. Sometimes that’s a goal. Sometimes we want to be able to appreciate someone’s art or music without thinking too much about the person and their feelings and their political views and perspectives. But I think in your case, that’s probably not the goal. Do you find that it’s hard for some folks in your audience to separate those two? Or maybe they try to and it’s not really comfortable for you?

BC: I don’t think about it much one way or the other. I think there’s a tendency for people who are at a certain distance to conflate the art with the artists. It happens with anybody that stands up in front of the public—they become larger than life and people read more into what they say that might actually be there. Or the image they project—sometimes the image is intentional, sometimes it’s just what people put on you.

That happens to me, to some extent, but in general the songs come out of my brain, my life and experience and feelings. And I try to have them be truthful. That said, there’s a lot about me that doesn’t go into songs, certain truths that I don’t think I really want to share with people. So you’ve got to allow for that.

If you think about Bach, nobody cares what his politics were. He just wrote all this beautiful music. I don’t know anything about his political views, if he had any. I think in the era in which he lived, if you were too loud in expressing political views that were not compatible with the authority around you, there’d be a terrible price for that. That would be true in Putin’s Russia. It appears to be, anyway. So you step away from politics. In the Stalinist period, in Russia, there was great music composed, too, where you really, really couldn’t take any chances. If you listened to Bertolt Brecht, you know, because of the content of what he wrote, what his political attitude was. But there it’s explicitly part of his art. That happens with people too, but I don’t know. I think if you live long enough, and work for over a long enough period, you’re gonna go through phases of understanding and phases of interest, and just be drawn into different areas: I’ve done a whole bunch of that, and now I want to do something else. That is going to affect how people perceive you and may not be directly related to what’s going on in your physical life at any one moment.

Yeah, and I’m thinking specifically of the spirituality aspect of your music and the political aspect that maybe for some people don’t line up in the same way that they do for you. I think that’s a challenge for folks sometimes. I know they’re part and parcel in your view, and in the music that you write and the messages you share, which I think is wonderful, but I think that probably is challenging for folks sometimes, who think, “I’m absolutely on board with this piece, and I just can’t quite reconcile with my own worldview.”

BC: The people who only associate me with “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” are divided into camps, basically. There’s the ones who think that’s cool, and the ones who hate it. I hear from both, and I’m aware of both, but that’s one song out of 300-odd songs that I’ve written. It came from a specific time and place in my life and in the lives of the people that I was with at the time. If I went to Central America now, I might write a song that had as much of a sense of outrage as that song does. But it wouldn’t be the same song, and it wouldn’t say the same thing.

The same would be true if you’re listening to “Wondering Where the Lines Are.” It’s a cute song, it may even be a good song, unless you actually listen to the verses. It’s as much about death as all the rest of my songs. It’s light. And it would be too bad if people thought that was the only kind of song I wrote. The same thing is true with “Rocket Launcher.’” There’s a whole lot of other stuff there, if you’re interested enough to pursue it. Don’t judge me by that one song. But I don’t take it back, either. I was there. That’s what I felt. It was the ease with which I felt that outrage that I wanted to share with my peers, who don’t experience stuff like that, or had not at the time. ‘Don’t judge people for taking up arms, if you don’t know what they’re faced with,’ was the undertone of that. I’m not suggesting that taking up arms is a desirable move to make. I think there are times when you can’t avoid it. That was what I wanted to share with people. I’m not a pacifist, because I think there are those occasions. But I think that peace is better than war, and love is better than hate. Most of what I have sung, and maybe will continue [to sing], tries to say that.

I’m thinking also of songs like “Call It Democracy,” which is one of my husband’s favorites. It came to him pretty early in life and was pretty influential in the way that he thought about and viewed things on a global scale. I don’t know if you would take any of that back, either, but it still seems to me a very powerful and still very pertinent commentary.

BC: I wouldn’t take it back. I think there’s more to the world than what that song says, but I think what it talks about is real. And it hasn’t gotten any better. Specific details change from time to time, but clearly it’s the economics of The Forever War, more or less. We didn’t think of it in that language when I wrote it, but it was the beginning of globalization, and I was seeing and hearing about the effects of it from the people who are being directly affected by it. I put that in the song, because you go to any place that was—whether it was Nicaragua, or Jamaica, or anywhere in Africa, or, you know, in a whole lot of other places—you can see the dark side of all that stuff, of the way we live. People who live there see it, too. They know exactly what the cause and effect is. Some of them have something to gain from it. Their leaders often have a vested interest in making deals with the developed world. But the benefit of those deals doesn’t go to the people. It goes to the actual signatories to the deal. That is a situation that is to the benefit of the corporate world. That hasn’t changed. So no, I don’t take it back or anything. I sing it once in a while, and people like it.

You can certainly disagree with any of these statements. I mean, people have different points of view. People who are among the ones that gain from the stuff… I mean, part of the point of “Call It Democracy,” of airing that kind of thought is, in North America and Europe, we’re all beneficiaries of this unfair system. And we should know that. You don’t have to go out and change anything. We might like it. But you should know where your stuff comes from. I still feel that way. But I don’t feel like I have to keep writing that song, though. There’s other things that jump up—some joyful and some not—that also need to be written about.

And that’s all part of being that witness, right? Of being that correspondent, sharing that experience and documenting and putting it out for better or worse? It’s still an experience that was very real for the folks that you were with.

BC: Yes. And for me, yes.

I have one more question for you: I’m looking at a very long, incredibly long list of awards you have received: Juno Awards, certified platinum records, Hall of Fame entries. What recognition has meant the most to you?

BC: Certainly not the music business awards. They’re all very nice, and the way I was appreciated by a number of people—that’s very gratifying. But it doesn’t go very deep. The Order of Canada, I think it’s probably the most meaningful way to be recognized. The honorary degrees are—I have a bunch of those now, and I’m about to get another one—those occasions are sometimes kind of fake. You know, you have a convocation, you gotta get somebody to speak at it. Sometimes there’s a deeper sense that the honor being bestowed is heartfelt. I got an honorary law degree in the same year, the same spring that my wife was graduating from law school. That was, that was pretty cute.

Awkward!

BC: Because she had slaved for three years to get this piece of paper, and I got one handed to me. But I got a doctorate in theology, that actually really meant something. Coming from Queen’s University in Ontario. That’s a couple of examples of probably the two things that actually did mean the most, of all those awards.

The Order of Canada Award—that’s a lifetime achievement award?

BC: It’s not exactly that. It comes from the government. There’s a committee that decides this year who should be included. They can induct a certain fixed number of people each year. They look around the Canadian scene for who’s contributed to the benefit of Canada. To be included that way—there are now several hundred people in the Order of Canada, maybe even 1000. It’s not business related—it has nothing to do with how many records I sold and stuff like that. I mean, indirectly, it does, because if I hadn’t, if nobody ever paid attention to me, I probably wouldn’t have been on the radar.

But to have it be seen as a contribution to the country is meaningful to me in a way that being feted for being a star of some kind is not. When I started, I thought being a star would be the worst possible outcome. A star quote, unquote. Just that term was offensive to me, because it seemed to me that anybody who’s seen as a star is not seen as a person. And I didn’t want to go there. I tried so hard not to have the kind of star image for the first few years I was doing this. But you can’t escape it. People are going to invest you with this larger-than-life thing, no matter what, if they pay attention to you. So, I gave up on that notion. But it’s so much more meaningful to be recognized for something beyond that.

Sure. Well, for someone who’s so focused on storytelling and sharing and contributing and giving back, I can see how that would be an outstanding moment of recognition.

BC: Yeah, it was cool. | Courtney Dowdall

Credit: theartsstl.com