Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar

Bo Carper – shakers

Janice Powers – keyboards

Instrumental

Composed: Easter Sunday 2018 (22 April 2018)

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar

Composed: MLK Day 2019 (January 21, 2019)

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar, chimes

Review:

Bruce Cockburn, a Canadian treasure, writes such thoughtful, pointed songs that it’s easy to overlook what a guitar virtuoso he is until he releases an instrumental album like “Crowing Ignites,” arriving on Friday. He wrote “April in Memphis” on Martin Luther King Day and it’s mostly solo except for the appearance of tolling chimes. The video sometimes displays King’s writings, while the music is a folky, elegiac rumination: fingerpicking, meditating, letting quiet chords resonate, drifting in and out of the blues, letting lone melodies keen in a private memorial. ~ from the The New York Times – Jon Pareles

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar

Colin Linden – dobro

Bo Carper – shakers

Constructed at the Firehouse – San Francisco – March 17 through 23, 2019

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – 12-string guitar, kalimba, sansula, charango, dulcimer, chimes, little-ass bells

Colin Linden – baritone guitar

composed circa 2016

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar

Ron Miles – cornet

Roberto Occhipinti – bass

Gary Craig – drums

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar

circa July 2018

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar, drum

Colin Linden – mandolin

Bruce Cockburn, Colin Linden, Janice Powers, Daniel Keebler, Celia Shacklett, Iona Cockburn – handclaps

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – guitar, dulcimer

Janice Powers – keyboards

Born in the Firehouse – San Francisco – March 17 through 23, 2019

Instrumental

Musicians:

Bruce Cockburn – baritone guitar, singing bowls, Tibetan cymbals, gong, chimes

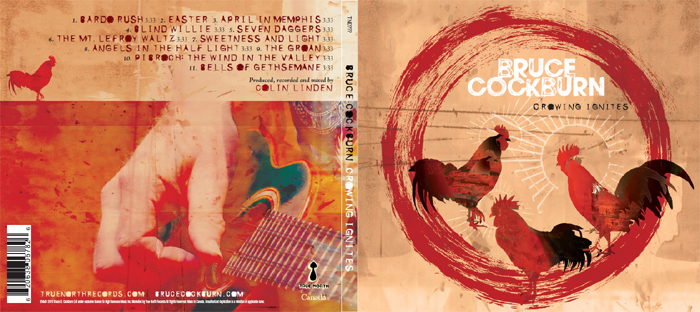

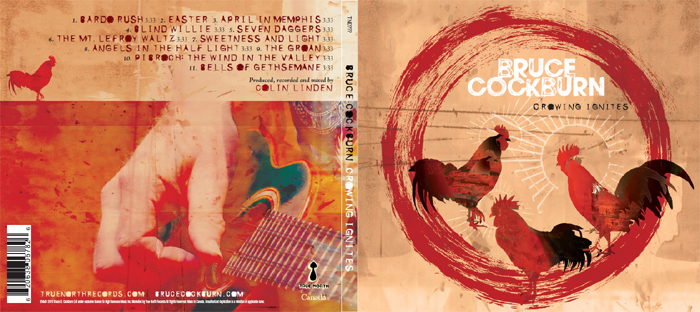

Liner Notes:

Produced, recorded and mixed by Colin Linden

Production assistance: Janice Powers

All compositions by Bruce Cockburn and Published by Holy Drone Corp. (SOCAN) © Holy Drone Corp.

Bardo Rush: bc guitar; Bo Carper shakers; Janice Powers keyboards

Easter: bc guitar. Conceived Easter Sunday 2018

April In Memphis: bc guitar, chimes. Composed MLK Day 2019

Blind Willie: bc guitar; Colin Linden dobro; Bo Carper shakers. Named for Blind Willie Johnson

Seven Daggers: bc 12-string, kalimba, sansula, charango, dulcimer, chimes, little-ass bells; Colin Linden baritone guitar. Constructed at the Firehouse. Nearby is a chapel maintained by the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, in which there is a statue of Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows, which gave the piece its title

The Mt Lefroy Waltz: bc guitar; Ron Miles cornet; Roberto Occhipinti bass; Gary Craig drums. Linda Manzer requested that I write something to go with the “Lawren Harris” guitar she built for her Group of Seven guitar project. This is it.

Sweetness And Light: bc guitar. A gift…there was nothing else to call this

Angels In The Half Light: bc guitar. In a dream, angels were girding me for battle against some sweeping darkness. They wanted to be honoured.

The Groan: bc guitar, drum; Colin Linden mandolin; bc, Colin, Janice Powers, Daniel Keebler, Celia Shacklett, Iona Cockburn handclaps. Les Stroud asked me to compose a score for his documentary La Loche. The first idea that came was this. We didn’t use it in the film, but it seemed to have its own life.

Pibroch: The Wind In The Valley: bc guitar, dulcimer; Janice Powers keyboards. Pibroch is the trance-inducing classical bagpipe music of Scotland. Whenever I hear it, somewhere deep in my being I’m on some rocky, windswept headland, sipping whisky from a scallop shell

Bells Of Gethsemane: bc baritone guitar, singing bowls, Tibetan cymbals, gong, chimes. Born in the Firehouse. Dark anticipation in a dark garden. Dawn looms, humming with trauma, pain and ecstasy

Recorded at the Firehouse, San Francisco, March 17 through 23, 2019.

Mixed at Pinhead Recorders, Nashville, April 14 through 18, 2019.

Mastered by Ted Jensen at Sterling Sound, Nashville, April 19, 2019

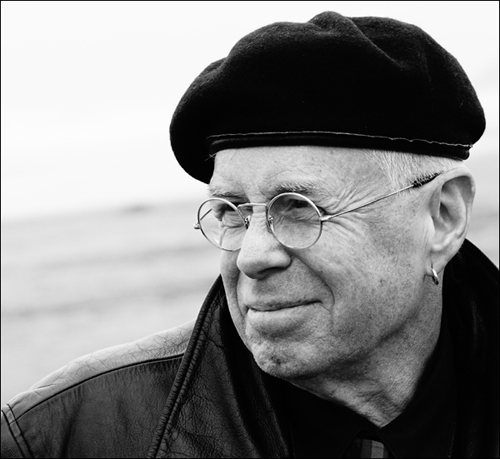

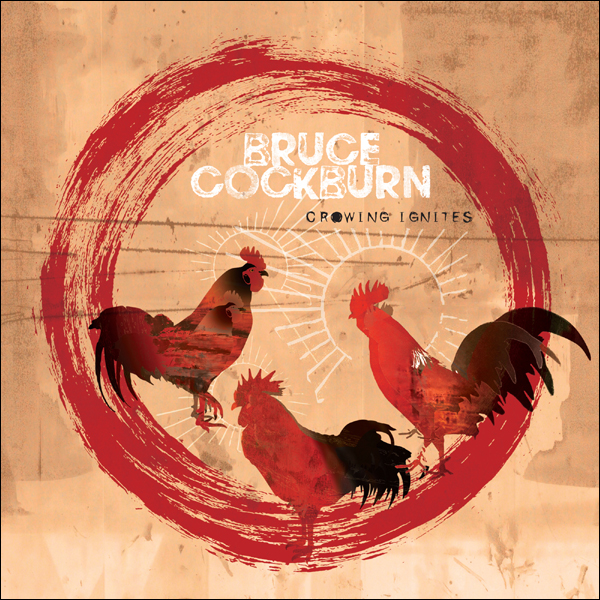

Album photography by Daniel Keebler

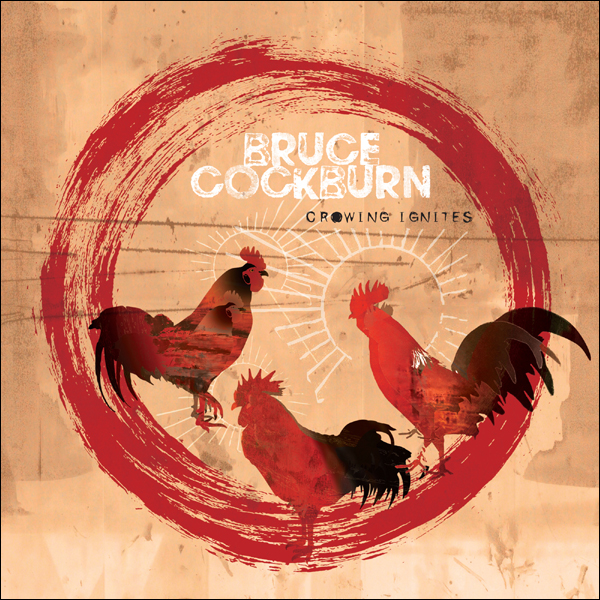

Art Direction design & layout by A Man Called Wrycraft www.wrycraft.com

Direction: Bernie Finkelstein bernie@finkelsteinmanagement.com

Thanks go out to Anne Germanacos, Colin and Janice, Boucher guitars, Linda Manzer, Les Stroud, Geoff Kulawick, Bernie Finkelstein, Daniel Keebler, Michael Wrycraft, Mike Stankiewicz, Celia Shacklett,

MJ and Iona,

and, above all, the Boundless

Bruce on the web: www.brucecockburn.com

Released 20 September 2019.

Album Note:

In the murky depths of time gone by, back when the Cockburn clan had chiefs, a chief of the Cockburn clan came up with the motto which adorns the family crest: Accendit Cantu. It’s Latin, and has been rendered in English as “Music excites” and “He arouses us by crowing”, among other variations. Having a hazy recollection of high school Latin classes, those seemed to me to be worthy approximations, but not exactly translations. When I looked up the original words, the phrase came out “Crowing Ignites”. Energetic. Blunt. Scottish as can be…

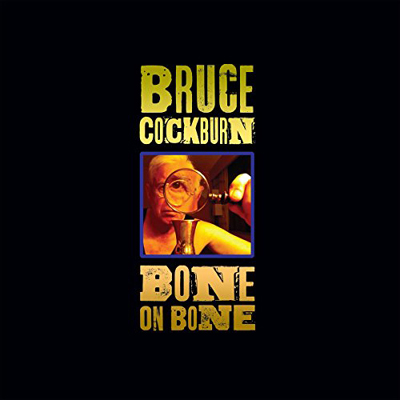

The catalogue #TND737

Bruce Cockburn – Crowing Ignites

Already, The New York Times had credited Cockburn with having “the hardest-working right thumb in show business,” adding that he “materializes chords and modal filigrees while his thumb provides the music’s pulse and its foundation—at once a deep Celtic drone and the throb of a vigilant conscience.” Acoustic Guitar magazine was similarly laudatory in citing Cockburn’s guitar prowess, placing him in the prestigious company of legends like Andrés Segovia. Bill Frisell, Django Reinhardt and Mississippi John Hurt.

Now, with the intriguingly titled Crowing Ignites, Cockburn has released another dazzling instrumental album that will further cement his reputation as both an exceptional composer and a picker with few peers. Unlike Speechless, which included mostly previously recorded tracks, the latest album—Cockburn’s 34th—features 11 brand new compositions. Although there’s not a single word spoken or sung, it’s as eloquent and expressive as any of the Canadian Hall of Famer’s lyric-laden albums. As his long-time producer, Colin Linden, puts it: “It’s amazing how much Bruce can say without saying anything.”

The album’s title is a literal translation of the Latin motto “Accendit Cantu” featured on the Cockburn family crest. Although a little puzzling, Cockburn liked the feeling it conveyed: “Energetic, blunt, Scottish as can be.” The album’s other nod to Cockburn’s Scottish heritage is heard on “Pibroch: The Wind in the Valley,” in which his guitar’s droning bass strings and melodic grace notes sound eerily like a Highland bagpipe. “I’ve always loved pibroch, or classic bagpipe music,” says Cockburn. “It seems to be in my blood. Makes me want to sip whisky out of a sea shell on some rocky headland!”

While Cockburn reconnecting with his Gaelic roots is one of Crowing Ignites’ more surprising elements, there’s plenty else that will delight followers of his adventurous pursuits. Says Linden, who’s been a fan of Cockburn’s for 49 years, has produced 10 of his albums and played on the two before that: “Bruce is always trying new things, and I continue to be fascinated by where he goes musically.”

The album is rich in styles from folk and blues to jazz, all genres Cockburn has previously explored. But there are also deepening excursions into what might be called free-form world music. The hypnotic, kalimba-laden “Seven Daggers” and the trance-inducing “Bells of Gethsemane,” full of Tibetan cymbals, chimes and singing bowls, are highly atmospheric dreamscapes that showcase Cockburn’s world of wonders—and his improvisational gifts on both 12-string and baritone guitars. Each track was wholly created in the makeshift studio he and Linden put together in a converted fire station in Cockburn’s San Francisco neighbourhood.

Singing bowls, Cockburn explains, are an endless source of fascination to him, dating back to a trip he took to Kathmandu, as seen in the documentary Return to Nepal. There, Cockburn stumbled on a man selling the small inverted bells sometimes used in Buddhist religious practices and became instantly captivated by their vibrational power. “I had no particular attraction to them as meditation tools or anything,” says Cockburn. “I just thought they had a beautiful sound.” After buying half a dozen in Kathmandu and more since, he now has a sizeable collection.

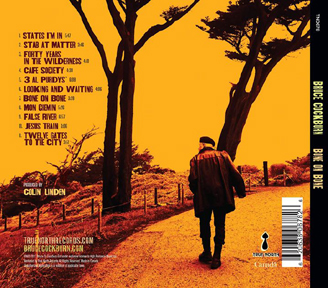

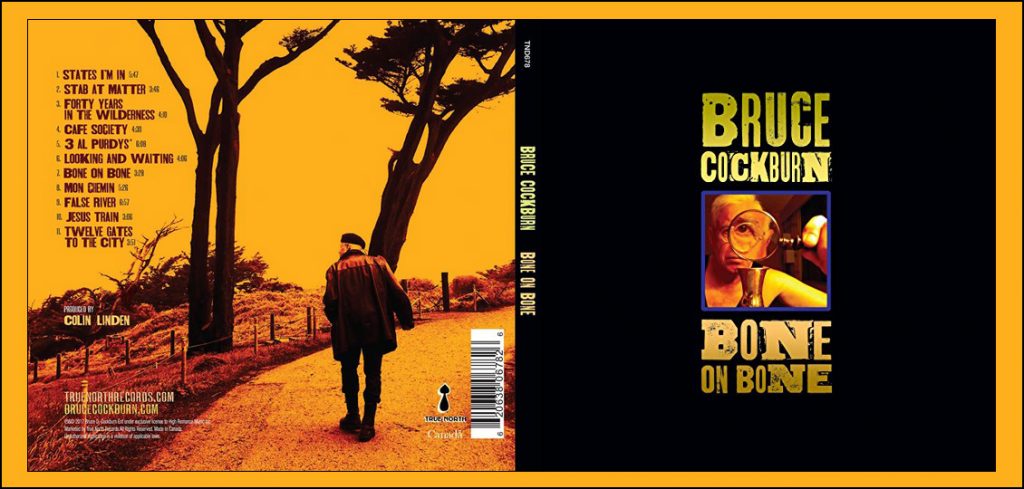

Two tracks on Crowing Ignites had their origins elsewhere. “The Groan,” a bluesy piece with guitar, mandolin and some collective handclapping from a group that includes Cockburn’s seven-year-old daughter, Iona, was something Cockburn composed for a Les Stroud documentary about the aftermath of a school shooting and the healing power of nature. And Cockburn wrote the jazz-tinged “The Mt. Lefroy Waltz” for the Group of Seven Guitar Project on an instrument inspired by artist Lawren Harris and custom-made by luthier Linda Manzer. It was originally recorded, with cornet player Ron Miles, bassist Roberto Occhipinti and drummer Gary Craig, for Cockburn’s 2017 album Bone on Bone, but not released until now.

Cockburn doesn’t set out with any particular agenda when composing an instrumental. “It’s more about coming up with an interesting piece,” he says. “Who knows what triggers it—the mood of the day or a dream from the night before. Often the pieces are the result of sitting practicing or fooling around on the guitar. When I find something I like, I work it into a full piece.”

“Bardo Rush,” with its urgent, driving rhythm, came after one such dream, while the contemplative “Easter” and the mournful “April in Memphis” were composed on Easter Sunday and Martin Luther Day respectively. “Blind Willie,” named for one of Cockburn’s blues heroes, Blind Willie Johnson, features a fiery guitar and dobro exchange with Linden (Cockburn has previously recorded Johnson’s “Soul of a Man” on Nothing But a Burning Light). And the idea for the sprightly “Sweetness and Light,” featuring some of Cockburn’s best fingerpicking, developed quickly and its title, he says, became immediately obvious.

Meanwhile, “Angels in the Half Light” is steeped in dark and light colors and conveys ominous shades as well as feelings of hopefulness, seemingly touching on both spiritual and political concerns—hallmarks of Cockburn from day one. “It’s hard for me to imagine what people’s response is going to be to these pieces,” he says. “It’s different from songs with lyrics, where you hope listeners will understand, intellectually and emotionally, what you’re trying to convey. With instrumental stuff, that specificity isn’t there and the meaning is up for grabs. But I’m glad if people find a message in the music.”

More than 40 years since he embarked on his singer-songwriter career, Cockburn continues pushing himself to create—and winning accolades in the process. Most recently, the Order of Canada recipient earned a 2018 Juno Award for Contemporary Roots Album of the Year, for Bone on Bone, received a Lifetime Achievement Award from SOCAN, the Peoples’ Voice Award from Folk Alliance International and was inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2017. Cockburn, who released his memoir, Rumours of Glory, and its similarly titled companion box set the same year, shows no sign of stopping. As his producer-friend Linden says: “Like the great blues players he admires, Bruce just gets better with age.”

~ True North Records

For further information, contact: publicity@truenorthrecords.com

Bruce Cockburn’s 34th album

Crowing Ignites

True North Records

Release date: September 20, 2019

Listen to / share “Blind Willie” from Crowing Ignites and pre-order here.

In 2005, Bruce Cockburn released Speechless, a collection of instrumental tracks that shone the spotlight on the singer-songwriter’s exceptional acoustic guitar playing. The album earned Cockburn a Canadian Folk Music Award for Best Instrumentalist and underscored his stature as one of the world’s premier pickers.

Already, The New York Times had credited Cockburn with having “the hardest-working right thumb in show business,” adding that he “materializes chords and modal filigrees while his thumb provides the music’s pulse and its foundation—at once a deep Celtic drone and the throb of a vigilant conscience.” Acoustic Guitar magazine was similarly laudatory in citing Cockburn’s guitar prowess, placing him in the prestigious company of legends like Andrés Segovia. Bill Frisell, Django Reinhardt and Mississippi John Hurt.

Now, with the intriguingly titled Crowing Ignites, Cockburn has released another dazzling instrumental album that will further cement his reputation as both an exceptional composer and a picker with few peers. Unlike Speechless, which included mostly previously recorded tracks, the latest album—Cockburn’s 34th—features 11 brand new compositions. Although there’s not a single word spoken or sung, it’s as eloquent and expressive as any of the Canadian Hall of Famer’s lyric-laden albums. As his long-time producer, Colin Linden, puts it: “It’s amazing how much Bruce can say without saying anything.”

The album’s title is a literal translation of the Latin motto “Accendit Cantu” featured on the Cockburn family crest. Although a little puzzling, Cockburn liked the feeling it conveyed: “Energetic, blunt, Scottish as can be.” The album’s other nod to Cockburn’s Scottish heritage is heard on “Pibroch: The Wind in the Valley,” in which his guitar’s droning bass strings and melodic grace notes sound eerily like a Highland bagpipe. “I’ve always loved pibroch, or classic bagpipe music,” says Cockburn. “It seems to be in my blood. Makes me want to sip whisky out of a sea shell on some rocky headland!”

While Cockburn reconnecting with his Gaelic roots is one of Crowing Ignites’ more surprising elements, there’s plenty else that will delight followers of his adventurous pursuits. Says Linden, who’s been a fan of Cockburn’s for 49 years, has produced 10 of his albums and played on the two before that: “Bruce is always trying new things, and I continue to be fascinated by where he goes musically.”

The album is rich in styles from folk and blues to jazz, all genres Cockburn has previously explored. But there are also deepening excursions into what might be called free-form world music. The hypnotic, kalimba-laden “Seven Daggers” and the trance-inducing “Bells of Gethsemane,” full of Tibetan cymbals, chimes and singing bowls, are highly atmospheric dreamscapes that showcase Cockburn’s world of wonders—and his improvisational gifts on both 12-string and baritone guitars. Each track was wholly created in the makeshift studio he and Linden put together in a converted fire station in Cockburn’s San Francisco neighbourhood.

Singing bowls, Cockburn explains, are an endless source of fascination to him, dating back to a trip he took to Kathmandu, as seen in the documentary Return to Nepal. There, Cockburn stumbled on a man selling the small inverted bells sometimes used in Buddhist religious practices and became instantly captivated by their vibrational power. “I had no particular attraction to them as meditation tools or anything,” says Cockburn. “I just thought they had a beautiful sound.” After buying half a dozen in Kathmandu and more since, he now has a sizeable collection.

Two tracks on Crowing Ignites had their origins elsewhere. “The Groan,” a bluesy piece with guitar, mandolin and some collective handclapping from a group that includes Cockburn’s seven-year-old daughter, Iona, was something Cockburn composed for a Les Stroud documentary about the aftermath of a school shooting and the healing power of nature. And Cockburn wrote the jazz-tinged “The Mt. Lefroy Waltz” for the Group of Seven Guitar Project on an instrument inspired by artist Lawren Harris and custom-made by luthier Linda Manzer. It was originally recorded, with cornet player Ron Miles, bassist Roberto Occhipinti and drummer Gary Craig, for Cockburn’s 2017 album Bone on Bone, but not released until now.

Cockburn doesn’t set out with any particular agenda when composing an instrumental. “It’s more about coming up with an interesting piece,” he says. “Who knows what triggers it—the mood of the day or a dream from the night before. Often the pieces are the result of sitting practicing or fooling around on the guitar. When I find something I like, I work it into a full piece.”

“Bardo Rush,” with its urgent, driving rhythm, came after one such dream, while the contemplative “Easter” and the mournful “April in Memphis” were composed on Easter Sunday and Martin Luther Day respectively. “Blind Willie,” named for one of Cockburn’s blues heroes, Blind Willie Johnson, features a fiery guitar and dobro exchange with Linden (Cockburn has previously recorded Johnson’s “Soul of a Man” on Nothing But a Burning Light). And the idea for the sprightly “Sweetness and Light,” featuring some of Cockburn’s best fingerpicking, developed quickly and its title, he says, became immediately obvious.

Meanwhile, “Angels in the Half Light” is steeped in dark and light colors and conveys ominous shades as well as feelings of hopefulness, seemingly touching on both spiritual and political concerns—hallmarks of Cockburn from day one. “It’s hard for me to imagine what people’s response is going to be to these pieces,” he says. “It’s different from songs with lyrics, where you hope listeners will understand, intellectually and emotionally, what you’re trying to convey. With instrumental stuff, that specificity isn’t there and the meaning is up for grabs. But I’m glad if people find a message in the music.”

More than 40 years since he embarked on his singer-songwriter career, Cockburn continues pushing himself to create—and winning accolades in the process. Most recently, the Order of Canada recipient earned a 2018 Juno Award for Contemporary Roots Album of the Year, for Bone on Bone, received a Lifetime Achievement Award from SOCAN, the Peoples’ Voice Award from Folk Alliance International and was inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2017. Cockburn, who released his memoir, Rumours of Glory, and its similarly titled companion box set the same year, shows no sign of stopping. As his producer-friend Linden says: “Like the great blues players he admires, Bruce just gets better with age.”

~ True North Records. Photo Daniel Keebler. Cover art Michael Wrycraft.