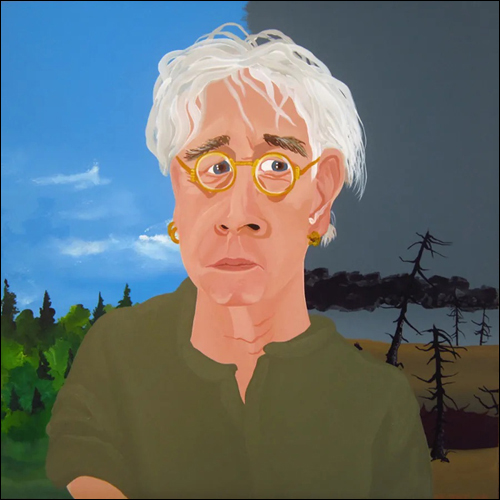

2 May 2023 – Bruce Cockburn has consistently upended rock and pop expectations across his long, storied career. The Canadian singer-songwriter, guitarist, and composer has released 35 albums since embarking on his journey as a professional musician in 1967. His material is often infused with deep meaning, including informed and complex perspectives on humanitarian concerns, politics, war, and spirituality. And he combines those views with sophisticated, melodically-driven music that’s enabled it to resonate with people from all walks of life and generations. The numbers speak for themselves. He’s had 22 gold and platinum albums, in addition to 30 charting singles in Canada, the US, and Australia.

Cockburn’s songs aren’t driven by backseat observations of the world. His activist and spiritual leanings have been front and center in his life for decades. He’s a devoted Christian but doesn’t communicate about his path from an evangelical approach. Rather, he lets his actions and outcomes inform his output, focusing on how adhering to positive Biblical teachings have value to everyone, not just Christians.

He’s spent a great deal of time working with Amnesty International, Friends of the Earth, OXFAM, and The David Suzuki Foundation—just to name a few organizations—in their pursuit of critical relief efforts. Cockburn has also been outspoken on issues including climate change, famine, native rights, and third-world debt. In addition, he has spent time in Cambodia, Iraq, Mali, Nepal, Mozambique, Nicaragua, and Vietnam to contribute first-hand to solving the issues those regions face.

His incredible life story was captured in his detailed and evocative autobiography, Rumours of Glory in 2014. A nine-disc box set of the same name was also released that year, chronicling his musical evolution.

At age 77, Cockburn continues propelling forward with his new album O Sun O Moon, and a lengthy tour to support it. The recording is about this moment in time, for Cockburn himself, as well as humanity writ large and the many struggles it faces. It explores the intersections of political manipulation, how spirituality is abstracted from its intentions to drive greed and tribalism, and generational responsibility for stewardship of the planet. Perhaps most importantly, it offers an outlook on keeping one’s own psyche intact during these times.

Cockburn spoke to Innerviews from his home in San Francisco, where he moved in 2011. He reflected on the inspiration for key tracks from O Sun O Moon within contexts ranging from the personal and existential to the global and societal.

To me, the new album is about priorities, focus, and spirit. What’s your take on the bigger picture it explores?

I think you’ve described it well. I suppose the focus comes from age more than anything else, but it’s also age in the time we’re living in. That latter aspect of it is normal for me. Pretty much all of my songs are responses to what I encounter. I mean, unless they’re fantasies. There are a couple of those in existence. But basically, my songs reflect the period of time in which they were being written and, in this case, that’s the COVID-19 and Trump era, with all this stuff that we’ve had flung at us.

You’ll hear me exploring myself as an older person in that context. There’s a lot of death on this record, but it’s not really specifically death itself. Rather, it’s the anticipation of the approach of that horizon and the kinds of feelings and thoughts that it engenders. The song “When You Arrive” is about that, but in my mind, it’s a kind of joyful song. Perhaps, darkly joyful or ironically joyful. I don’t see this as a dire thing, but it’s an important thing, worthy of attention.

The song “O Sun by Day O Moon by Night” also reflects a positive perspective on our inevitable departure. Tell me about the peaceful view it communicates.

Well, I think the negative perspective is everywhere. We entertain ourselves by watching thousands of departures over our lifetime on TV and elsewhere. But for me, it isn’t another step. I don’t really know what’s going to happen. My own belief is that I will be at least faced with an opportunity to get closer to God. What does closer to God mean? That’s pretty vague. I don’t believe in the Pearly Gates, although the dream in the song you just referred to kind of goes there. Rather, I see all that as symbolic and so I don’t really know what it’s going to be like.

At the very least, the energy that is contained in your body is going to go out to the universe and you do literally become part of everything. I mean we are now too, but we don’t know it because we feel like discrete creatures, but at the point of death, there’s a big change that happens.

So, either way, I think the manner of going is the part that scares us and the part that is too often tragic, and sometimes horribly inflicted on us. But the result of the departure I think can be approached with joy, or at least with kind of joyful anticipation. Not that I’m in a hurry or anything, but I think since it’s inevitable, death is as much a part of life as birth.

“On a Roll” captures a productive, yet realistic worldview at age 77. Talk about the drive and determination it illustrates about you at this moment.

The adventure continues. I don’t take any of it for granted. I do think that it’s going to hit the wall at some point. The hands are going to stop working or something else will happen, but for now, I’m able to keep doing this stuff and I think it might have partly to do with having a young daughter. So, I’m experiencing parenthood again in a deeper and more meaningful way than I did the first time around. She’s 11. I also have an older daughter who’s 46. So, I’m coming at it from a whole different perspective than when I was younger. It’s much more welcome and less fraught this time around, even though the world seems to have more to be fraught about as parents, now. Even though I don’t feel like a particularly young guy, I’m experiencing a lot of aspects of what it is to be a young adult in this culture.

I also get a lot of energy from the people who listen to the songs, and those who come to shows. I like playing for audiences and I like the travel and always have, so that hasn’t changed.

I feel like I’ve been led through the life that I’ve had and that continues, and I don’t really try to second guess it. I don’t take it for granted. It could stop anytime, but I don’t know, it’s a cliche to say, “I’m living in the moment,” but it has something to do with that.

And also, I feel like the journey isn’t over yet. I could see how you could get there. I think if I were by myself at this age and didn’t have a loving family to be in, that might be pretty depressing. Depression sucks up energy like nothing else. I think a lot of people do get depressed because the energy levels go down. They have for me too, but that’s offset by fresh things happening, so I guess it’s easier to deal with.

“Orders” explores how religion continues to be twisted to serve negative agendas, despite many of them stating we’re supposed to embrace one another, regardless of differences. What are your thoughts about how music can help transcend the socio-religious divides of the world?

I’m not confident that music can change anything, but it would be nice if it did of course. You can never carry that notion too far because you don’t know. I do hope that people will be encouraged by “Orders” and what it has to say. It’s one thing to sit there and say, “Oh yeah, we’re supposed to love thy neighbor,” but Christians have been failing to live up to that for 2,000 years. And there’s no reason to think we won’t keep on failing at that. But it doesn’t hurt to be reminded every now and then, that’s what we’re supposed to be doing.

Christians are under orders to do this, and we should be paying attention to that. And then you start thinking, “Well okay, well what does that mean? Who do I have to love?” And “everybody’s” too vague, so I just started giving examples in the song.

After decades of songwriting, what are your thoughts about making messages like that universal, without being didactic?

It’s a balancing act, because it’s easy to slip into preaching, and I’ve been accused of that at times. It’s always concerned me, and I feel like I’ve always had to make an effort not to go there. When you just say some things out loud, it sounds like you’re preaching just because of the nature of the material you’re spouting. People don’t always want to hear my opinion about things true or not. Of course, I think what I’m saying is true, but others might not agree. I do think you’re much more likely to be heard by people if they don’t think you’re preaching at them.

If you go to church or another religious institution, you expect to be preached at. You’ve volunteered for that, and it’s fine. But outside that context, it’s usually on an unwelcome thing. So, what I try to do is just share what I think and feel, and as long as people understand that that’s what it is, then they can take it or leave it. They don’t need to feel preached at. I’ve been blessed with an audience over all these years that’s willing to listen to this stuff and to varying degrees absorb it, and I’m totally grateful for that.

You emerged as a professional musician in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when activism and confronting difficult truths was more common. There’s a lot less of that these days. What’s your view on that shift?

You could also include the word “fashionable” in that. In the ’60s, a lot of people were sounding off because it was fashionable. When it stopped being fashionable, they stopped doing it. Not everyone and the real artists, in my view anyway. The ones who haven’t died have kept that up. They maybe had a different emphasis because times change, and we all change to some extent with them. At least our sense of how we fit in things tends to change.

The media, and radio—which is almost weird to talk about anymore—has relatively little importance in any area, except for the obvious pop stuff. I listen to rock stations when I’m driving my daughter to school because that’s the music that she likes to listen to. There’s some good stuff in there. Some of it’s not very good, and none of it really addresses much of what I think is worth addressing.

But then I think when I was a teenager, and even before that. I wanted to listen to Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, and they weren’t talking about anything very important either. It was a little grittier, at least with Elvis’ songs, because he covered so many great blues artists, or at least drew so much from that world.

Pop music’s always with us. ABBA’s had a resurgence. Who could have imagined that? Back in the ’70s, that was kind of a pet hate of mine. Not ABBA specifically, but that part of the music world they represented. I had no use for it at all. They were making effective pop records that were really successful and that’s fine. Taylor Swift is also doing that, but I think she’s a better songwriter than the people in ABBA. I hope as she matures, that maturity will apply to her songwriting, because I think she’s good at it.

There are many capable songwriters that perhaps aren’t living up to what I imagined their capacity to be. But that’s my imagination talking. Really, I don’t know. Once in a while it seems like there’s been a window in which radio has accepted other kinds of music other than very produced, commercially-directed kind of stuff. And then the window closes after a while when the radio station changes hands and the new owners want more money, or when somebody discovers that they can make more money doing something else.

I’ve been lucky that I’ve been around for a couple of those windows to open and close again. Each time one opens, the audience gets a little bigger and, in my case, it seems like most of the people that have been drawn into my thing have stuck with me.

“To Keep the World We Know” addresses climate change and the idea of looking beyond ourselves. Explore its origins.

The actual song came about because Susan Aglukark called up and wanted to write a song together, and I thought it seemed like a good idea. We had a good time working together on it. The title was mine, but the idea of the world being in flames was hers. We’re seeing all this drought and wildfires all around the world, and it just seemed like something worth writing about.

You think about the future differently when you’re the parent of a young child. I think it’s because there’s an emotional investment in the future that you can’t ignore. With my daughter, the topic comes up tangentially from time to time. There’s no particular agenda. It’s about just paying attention to what’s going on. We talk about it a lot in terms of what she encounters, more than what I encounter. I have a perspective that is different. I’m considerably older than my wife as you can imagine, and so her perspective and mine are also different from each other, but I think mutually complementary.

So, I hope that what we can offer to our daughter is to be useful and that each of our excesses can be tempered by the other. Hopefully, we come up with some sort of reasonable advice and a reasonable context for our daughter to grow up in.

O Sun O Moon has an instrumental titled “Haiku,” and you’ve done two all-instrumental albums in recent times with Speechless and Crowing Ignites. How do instrumentals communicate in a unique way for you?

I think if you have lyrics, you hope if a person’s paying attention to those lyrics, they’ll be drawn into whatever it is they’re about. When you listen to music that does not have lyrics, that doesn’t happen and you’re free to feel whatever the music brings out in you.

I’ve always felt like there was a sense of space that went with instrumental music that doesn’t typically happen with songs with lyrics. If I listen to Bob Dylan, I’m thinking about what he’s saying, as well as savoring the music and whoever’s playing on the record. But if I listen to Japanese flute music or Bach, I’m not doing that. Rather, I’m allowing myself to be transported to wherever that music takes me. For me, that’s often a kind of deliciously-wistful poignant infinity. There’s a sense of that physical space almost. It’s imaginary, but it feels physically combined with time stopping. If you’re seriously listening to something, time stops. Those are the powerful effects I really notice with almost any kind of instrumental music.

Tell me about the choice of musicians on the album and the approach you took when recording them.

I really had a great time listening to what everybody brought to it, and I could do that partly because of the way we recorded. We first started with just me and Gary Craig playing drums and percussion, and once we had that down, we brought everybody in to add to it. So, it was fun to get the songs initially recorded, but the great thing about that was I had the luxury then of sitting back and not worrying about my own performance while listening to what everybody else brought in.

Colin Linden, who produced the album, had a great part to play in the choice of musicians, but we talked about it a bunch beforehand as we’ve done with previous albums. The core band included Victor Krauss on bass and Gary on drums on most of the tracks. Colin came up with Jim Hoke on marimba, clarinet, and sax, and Jeff Taylor on accordion and dolceola.

Jim brought so much to the recording in terms of horn arrangements and marimba playing. It was my idea to have marimba. I’ve always been a fan of Martin Denny and it seemed like some of these songs would suit that kind of sound, and it worked out.

We also have Sarah Jarosz on mandolin, Jenny Scheinman on violin, and Allison Russell, Shawn Colvin, and Buddy Miller on harmonies. I think this was the first time I’ve worked with Buddy, though I’ve met him many times. So, it was great to get him on the album.

It was really cool and a lot of fun to build the album up the way we did it. I kept getting pleasantly surprised by the results.

This wasn’t the first time I’ve worked this way. The albums I did with T-Bone Burnett, including Nothing but A Burning Light and Dart to the Heart, started in a similar way. For Nothing but A Burning Light, many of the songs were done with just me and a programmed, electronic drum track initially. Then we’d replace the fake drums with the real ones. It’s an easier way to get things done.

With Bone on Bone from 2017, we recorded that all live with the band, in the exact opposite way. We put the band together, got everybody in the studio, and just played, with some overdubs.

Either approach can work. If you’re dealing with a lower budget, the approach we took for the new album is good, because you don’t have to pay for people to wait around while you figure out what you’re doing.

We did have a decent budget for this album. But it felt like the approach we took was a better way to spend the money, and it works just as well, creatively. It’s different, though. You don’t get the same sort of spontaneous interplay that you might if you were actually playing live. The lucky accidents are less likely to happen, but on the other hand, you have more control over what happens, too.

Provide some insight into your creative process.

I still just love the guitar. So, sometimes when I’m playing, an idea will come that wants to be an instrumental piece. A riff or ideas that come one after the other can become the bones of an actual composition, and then I’ll chase that down and come up with something else for it. So, over the years, there have been quite a few occasions like that.

Writing instrumentals is different from writing songs where it’s all about lyrics. I like the sense that instrumental music offers something open to the listener’s interpretation. And playing the piece offers something similar to the performer, without being pinned down to specific lyrical ideas. It feels freer in a way. It’s nice to have instrumental things to do.

Of course, I like writing songs, too. When I write a song, I tend to structure things more formally and I tend to write the guitar parts into the song as a composition. So, I kind of play the same way through it, allowing for the occasional solo in the middle of the song. With the instrumental pieces, I still play them the same way, probably, but there’s more of a feeling that this could go anywhere, especially when you get to play it with other people. You just think, “Yeah, we’re jamming now. This is good.”

What are some of the key challenges you face in your creative process these days, and how do you transcend them?

The challenges are mostly physical. I’ve got arthritic fingers and sore feet, and whatever stuff that goes with being older. Eventually, those things might become impossible to get past. They are obstacles, in a way. Some of the older songs that are very simple I can’t play anymore because my fingers just won’t make the shapes I need to make. But that’s minimal. I foresee there will be a point where the songs I can’t play start outnumbering the other ones, and then it’s probably time to retire, but we’re not there yet.

The only other thing that I might put in that challenge category is having to come up with new stuff all the time. Having to do so is a choice, of course, but I don’t want to keep writing the same song. The more I write, the less room there is to come up with new stuff it seems. As much as we can add onto ourselves or subtract from that, as the case may be over time, you’re still essentially the same person you were when you started out, and you feel the same way about a lot of things and have the same vision. So, how do I say whatever it is I want to say without repeating myself excessively? Some repetition is going to show up. So, that comes into it in the writing of a song. Sometimes, I’ll catch myself at it. I’ll write a line, I think “Yeah, that’s cool,” and then be like, “Wait a minute, I said that 20 years ago.” And so, the question becomes, “Okay, well how can I say that in a fresher way?” I’m always still just figuring out how to write a good song.

When you perform solo, you occupy your own unique universe, surrounded by an expanse of instruments and technology. Describe your setup.

Solo concerts are mostly what are coming up this year. I have multiple guitars, because there are multiple tunings. I don’t want to inflict retuning over and over on the audience. I like being able to pick up ready-to-go guitars and just play. I also like the diversity of sounds. There’s the 12-string and dobro, which bring different sounds to the shows. They offer sonic relief from hearing the same kind of guitar sound throughout the night.

It’s a comfortable setup. I have cables, and little bits and pieces of stuff on a table near me, so I don’t have to hunt for things in my pockets or kick the water bottle over to get to them. I’ve also got a little collection of effects pedals to add variety to the mix.

With the acoustic solo shows, it’s about keeping the sound of one guy’s voice and guitar from being too monotonous over the course of the evening. The outcome is also a product of what happens between me and the audience, too, not just the physical stuff on the stage. It’s as much about what the audience gives back, and what I’m able to give back to them as a result.

I use in-ear monitors, because they’re better for my ears, and much more controllable for whoever’s mixing the house sound. They let me hear what the audience is hearing. I need to have that perspective, to have a sense of what I’m throwing at people.

Do solo concerts offer a greater level of freedom compared to ensemble shows?

In theory, they do offer a little more of that. I tend to do things the same every night once I settle on a set that works for me. The shows tend to be the same night after night, with minor exceptions. But theoretically, that freedom exists, if I were not as inclined to want to stick to a pattern. But that’s my nature. I’m just more comfortable when I’m not fretting over whether I’m going to make bad choices as far as the order of the songs go, or just forget what I know.

For the first decade I played solo, I was more spontaneous. I had a list of all my songs on top of my guitar, and I would just look down at that list and think, “Okay, well this one has the capo here and it’s in this key and it’s up-tempo, and I just did a couple of slow ones, so I guess I’ll do this one now.” But that was very stressful sometimes, because sometimes you just look at the list and go “What do I do now?” So, I like it better when I’ve got some sense of flow. I can change it if I want, but when there’s a planned show, my current approach works better for me. It’s also better for the lighting person. I can tell them what to expect and set up cues accordingly. It’s helpful to have things organized like that when I have a band, as well.

This is just my way of doing things. I tend to have a greater need to have the set structured. I can easily imagine being in a band where you didn’t do that. I’ve seen Colin Linden play with his bands where he’ll just turn around and yell out a song title and then they’ll play it. But these days, I feel it’s more practical to have a set list.

You’ve witnessed myriad technological transitions in the music industry across your career. What’s your perspective on its current ability to effectively compensate musicians, and the directions it appears to be heading in?

“Effectively compensate” are the key words. It’s one of the basic ingredients of human existence, and it’s certainly true in the music world. Lately, it’s an issue because of streaming and the fact that it doesn’t really pay royalties. That’s a concern and it has made life harder for musicians. In a sort of good way, it’s put the emphasis on live performances, which is okay because I think that’s when the music is at its most real. But yeah, it would be nice if the various powers that are working on these things could successfully persuade the streamers to pay up.

The music scene has changed totally and it’s still in flux. I don’t think it has settled anywhere yet. All of a sudden, we’re getting AI imitations of famous people. There was an actual virtual pop star in Japan a few years ago. This stuff has been written about in sci-fi books before, but it’s actually happening, and there’s going to be more of that.

Who actually needs humans when you can create a holographic image of somebody that just sounds really great singing and doing whatever? But it won’t replace us in the short term, at least. As I heard myself saying that, I was thinking of the old music union guys in Ottawa that were very upset when people started using synthesizers. They felt they would take jobs away from musicians, but it hasn’t really worked like that. AI probably won’t either, but things are changing all the time. I’m not interested enough in the electronic side of things to want to explore that.

It’s not that you can’t make good music with machinery. You can, but it’s not the same as when people do it. With AI, its function may change too. All of society is moving in the direction of standardizing, unifying, and homogenizing everything. But of course, in our movement in that direction, we’re also dealing with elements of chaos, such as mass shootings, war, and pandemics that work in the opposite direction. Politicians use the fragmentation for their own gain. It’s hard to say if music’s going to reflect all of that and where it’s going to go. I have no idea. I won’t be around to see it.

I mean things never stop. They’re constantly in motion and they’re never going to land anywhere, as long as we’re people with some capacity for imagination. Things are going to keep moving forward and changing. What I do know is things are hard now for musicians. I wish it was easier for musicians to make a living playing music, especially young ones getting started.

Those of us who’ve been around for long enough to have an audience are not in as difficult a situation, but if I were starting out now, how would I get heard? Where would I go? I could put stuff out online and maybe I’ll get lucky, and somebody will notice it. But millions of other things are coming out at the same time. You can find good stuff online, but there’s a lot of amateur attempts that you have to weed through to get to the good stuff, unless where you know what you’re looking for.

Do you plan for the long term with your career or is it more of a case of going with the flow?

The songs on the new album have been in progress for the last couple of years, and it’s just about to come out. So, it’s going to be the focus for the short term. It’s not new for me to be in this position because I don’t really plan ahead with respect to songwriting at all. Once in a while, I have the feeling that I want to go in a particular direction, but that is usually really just about a particular song. Should it be focused on electric guitar or acoustic guitar? What kind of music do these words want? But in terms of the big picture, I’m not much of a planner. Right now, we’ve got gigs booked across the next 12 months, and that’s about as far ahead as I’m taking it. We’ll see what happens creatively between now and then. The field is wide open.

~from www.innerviews.org – Anil Prasad