By M.D. Dunn

February 14th, 2018

At age seventy-two, after fifty years of recording, Canadian songwriter/guitar wizard Bruce Cockburn has produced some of the best music of his career on September’s Bone on Bone. Over thirty-three albums, Cockburn has offered fearless commentary on political issues, meditations on spirituality, and hundreds of brilliant songs that defy categorization.

He is perhaps best known for two mid-career hits, 1979’s “Wondering Where the Lions Are” and 1984’s “If I Had a Rocket Launcher.” These songs, as different as they are from each other, are representative of Cockburn’s sprawling catalog. “Lions,” with its reggae-influenced rhythms is a showcase for his unique finger-picking style, and “Rocket Launcher” demonstrates a concern for social justice that runs throughout his songs. (Indeed, he brought politics into his art when musicians were encouraged to avoid “causes.” His involvement in the anti-landmine campaign helped bring about the Ottawa Treaty, in which 122 nations agreed to abstain from using the weapons.)

Admired by musicians and activists around the world, he is royalty in his country of birth. Yet, for all the critical acclaim, Cockburn is a humble working musician with a generous sense of humor. Of his legendary status, Bruce Cockburn has said: “You can be a legend, or you can be present. You don’t get to be both.”

In a recent interview, conducted over telephone, Cockburn discusses his music, songwriting, and the benefits of not selling out.

The Rumpus: How are things in California? From the outside, it looks terrifying.

Bruce Cockburn: San Francisco is such an anomaly in every sense: culturally, weather-wise, and in terms of its sociopolitical structure. As a city, it’s kind of all by itself, with the illusion of self-sufficiency. You’re insulated from a lot of the weirdness. One day, we won’t be. There will be that big earthquake, and it’ll be our turn.

Rumpus: Bone On Bone is a beautiful album. It gets more interesting with each listen. After about two plays, I could remember most of the lyrics, which says something about the strength of the writing.

Cockburn: I find it surprising you could remember because I have my difficulty with them. It took me a while to get it. I still struggle with the spoken word parts on “Three Al Purdys.” Of course, they are not my words, they are his. But it’s always touch and go if the lyrics are not just simple rhyming couplets.

Rumpus: That is such a cool song. Having Al Purdy’s poems “Transient” and “In the Beginning Was the Word” with verses from your narrator [a homeless performer of Purdy’s poems offering “three Al Purdys for a twenty-dollar bill”] is remarkable storytelling. Your verses in the middle fit perfectly with the verses from Purdy’s poems. My only complaint is that there are only two Al Purdys in a song called “Three Al Purdy’s.”

Cockburn: Well, I didn’t get the twenty dollars. Nobody was forthcoming with the twenty-dollar bill.

Rumpus: Your playing and lyrical approaches seem to change with every album. Bone On Bone might be the album that catches your live sound most accurately. It doesn’t sound like anything else you’ve done, but has some of the paranoia of The Trouble With Normal, with the roots music feel of something like The Further Adventures Of.

Cockburn: That’s interesting you say that. My young daughter used to insist on listening to my stuff in the car. Every time we got in the car, she’d say, “Daddy, can we listen to you?” So, I’d be like, “Oh, okay. Are you sure you wouldn’t like to listen to someone else?” A fan had given me a three-CD set of her “Best of” choices covering the 70s, 80s, and 90s. I ended up listening to the 70s disc of those while driving my daughter to preschool. There were a lot of songs on there that I wouldn’t have thought to collect and others that I was surprised were missing. It was nice to hear how those records sounded after all these years. They are all very different.

The albums from the 70s sound very different from the ones that came after, and Inner City Front. Those were all Gene Martynec productions. There is something about the way we made those albums. I didn’t have a sense of it at the time, I don’t think. But it was interesting to listen to them. That period and that way of recording definitely impacted the songwriting and the approach to Bone On Bone. We didn’t attempt to reproduce those albums, and I wouldn’t remember enough about what Gene did in the studio to be able to reproduce them anyway. But my attitude going in was I wanted to get something like that feel back, the less structured, less produced kind of feel. I think in the 80s we got very far away from [a stripped down] feel. It came back since the T Bone Burnett albums [Nothing But a Burning Light, Dart to the Heart] in the early 90s, which were, in spirit, more like the 70s albums. I haven’t really bothered thinking it through enough to articulate it well, but I do recall thinking I wanted to make an album like those albums.

Rumpus: Did you record Bone On Bone live with the rhythm section?

Cockburn: Yeah, everything. We had a few overdubs, but the songs were recorded complete with everyone playing.

Rumpus: Do you record on tape?

Cockburn: I think we did on this, pretty sure. I didn’t take much of a hand in the production. I used to worry about that more in the 90s when Colin Linden first started producing my stuff. I insisted on being co-producer at least in name so that I would have veto power over things, or more than just the power of veto is what I was thinking. But after a couple of albums, it was obvious that Colin was doing all the work and so should get the credit. It’s a process in which I have a great involvement anyway, but I trust Colin’s expertise and Colin’s ears and don’t think much about the technology end of it. The last bunch of albums we’ve done both digitally and with tape.

Rumpus: It captures your live sound more faithfully than many of your studio albums.

Cockburn: The studio was great. It’s a studio called Prairie Sun near Santa Rosa, an hour north of San Francisco. It’s an old chicken ranch. The studio is in the old farm buildings. The smell of chickens is mercifully long gone, but the atmosphere is great. And the sound in these old buildings is good.

Rumpus: You’ve said the title of the new album is a reference to arthritis. In other interviews you’ve said there are pieces you can no longer play. Have you had to adjust songs so that you can play them?

Cockburn: In one case. It’s partly arthritis and partly just wear-and-tear. The cartilage is gone from using the joints too much. A song like “Peggy’s Kitchen Wall” took me a long time to learn to play again because the shape of my hand has changed. The fingers don’t point in the same way. I don’t have quite as much reach as I did. There’s a riff in the original version of “Peggy’s Kitchen Wall” that was just a millimeter beyond my reach. There is one note in that riff that I couldn’t get to, so I stopped playing the song. Then I figured out a different fingering and tuning to be able to play it again. That song’s back in the repertoire.

It’s more common for me to just not play those songs. For example, I can’t play “Foxglove.” Not that I particularly miss it, because I’ve played it a lot, and there are other songs I want to play more. The rolling three-finger movement on the right hand is something I don’t do so well now, so songs that involve that tend to get left out.

Rumpus: Has the limitation opened new possibilities on the guitar?

Cockburn: It’s maybe changed the emphasis a little bit. The new album is more bluesy than most of my albums. The guitar, at least, is approached that way. It’s more about getting into a mindset than it is about the hands at this stage. I mean, I can still play most of what I want to play. I haven’t had to make a major enough adjustment for it to affect the songwriting.

Rumpus: That right-hand technique of yours with the extended pinkie, like a shaka sign, is painful to execute and seems to concentrate the movements of the second joints of the first, second, and third fingers. To hold that position for any length of time is painful. I can only imagine the damage sixty years of playing that way would cause.

Cockburn: The worst part is the thumb. One time, someone wrote a review of a show in which they observed that my guitar playing was like a bunch of events happening, held together by my right thumb. When I read that I thought, Jeez. He’s right. If anything happens to my thumb, I’m screwed. This was not that long ago, maybe ten years ago, but I could see this portent: there were going to be issues. And I’d never thought about it before that. Sure enough, there are issues. But, so far, I’ve been getting away with it.

Rumpus: How much do you play when you’re not on the road?

Cockburn: Less than I should, and less than I want to. I am busy at home the way our lives are set up at this point, with my wife’s working hours and my daughter’s school hours, and bedtime hours, etc., etc. I have to fit my playing time into a relatively short day, and still get the errands done. Ideally, I’d be playing four to six hours a day. I’m lucky to get in ten to twelve hours a week. I catch it when I can.

Rumpus: Are your songs usually fully formed when you go into the studio?

Cockburn: They are pretty much done. I don’t think about recording until I have a body of songs that feels like it’s ready to record. There are occasions when there have been revisions in the studio, or when I hear something back that doesn’t work, and I have to figure something else out. But that’s not true of this album. All the songs were as you hear them.

Rumpus: Do you change strings before every performance?

Cockburn: I used to, but not anymore. I change guitars so often during a show that the strings last longer. Back in the day, when it was one guitar through the whole show, I changed them before every show. But now, with everything plugged in, the age of the strings is much less an issue than it used to be. Your sound isn’t dependent on the string singing into a microphone.

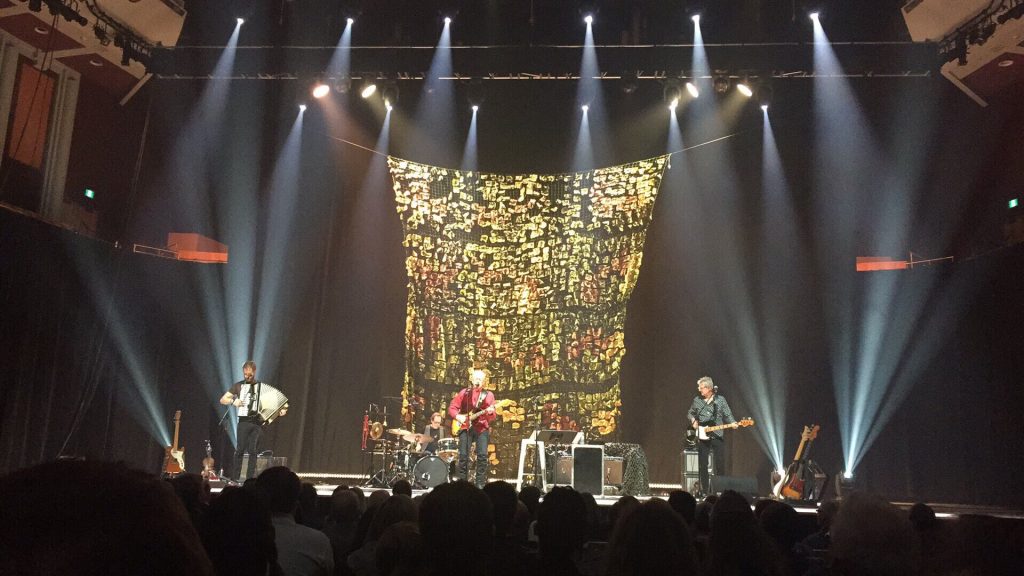

Rumpus: What is the story about the backdrop you use live?

Cockburn: It’s just a piece of camouflage netting. It’s probably going to be retired after this tour. We’ve been using it a lot.

Rumpus: Is it military issue?

Cockburn: Yeah. It’s somebody’s military. I don’t know whose. I don’t think it was Canadian-issue, maybe it was. I got it in a surplus store somewhere.

Rumpus: When your first album came out in 1970, you entered into the height of the music industry. I know it was different in Canada, where the scene was still developing, and Bernie Finkelstein [Cockburn’s manager and one of the architects of the Canadian music industry], and True North Records, as well as government-regulated quotas for Canadian content were helping with that. And you enjoyed a couple of decades early on of that abundance, but it all seems to be gone now. When I was a kid, we would complain about musicians who “sold out,” meaning that they had a commercial success with a questionable song, or that they sold their songs to corporations. But you never sold out. Was it for the lack of offers?

Cockburn: No, it wasn’t, actually. The offers were never numerous, but there were many requests over the years to use songs. I remember getting an offer from a major credit card company that wanted to use something. This would have been in the 80s, when my songs were getting quite a bit of airplay. I remember thinking the money they offered was insulting. Never mind the issue of selling out, which would have been enough for me to say no, especially to a credit card. But they just offered this crappy, token sum of money for the use of a song in an ad. Once you put a song in an ad, you could never sing it again. I mean, back then! Nowadays, you do. Now, those are the songs that become hits for the people who do that.

In my aesthetic/ethical frame of reference that would mean the death of a song. If I am going to kill a song on your behalf, you’d better give me good money for it.

Bernie and I talked about this way back, and we talked about it every time any kind of publishing deal came up. When I sold my publishing before moving to the States, for example, there was a stipulation in the contract that the songs can’t be used for political or commercial purposes without my permission. So, if a non-profit wants to use a song, odds are we’ll give them permission, depending on what they are trying to convince people of, I suppose.

But the concept of “selling out” is an outdated one anyway. It might come back. It isn’t an outdated idea for me personally. I still feel very strongly about it. Looking around, the sensibility that taught me to think that way is not readily noticeable anymore. Young people are growing up with a different idea how to do it.

Rumpus: Do you think that is because there is not as much money available through record sales? That sales allowed musicians to turn down commercial offers?

Cockburn: That would probably exacerbate it, I’m not sure. But I think people just dropped the idea. You don’t hear anybody talking about it. As you pointed out, back in the day, people did talk about [the commodification of music]. You’d take somebody to task for having done that, or for considering doing it. You’d go to great lengths to avoid the appearance of selling out, even if you weren’t. It’s just not on people’s radar now.

Rumpus: I am very proud that in thirty-six years of writing songs, I haven’t “sold out.” Then again, I haven’t had the opportunity to sell out, so I don’t know how I’d stand up to the temptation.

Cockburn: [Laughs] Faced with a mountain of debt and a tempting offer, who knows? It’s a judgment call that each of us has to make for ourselves. It’s not fair to pass judgment. Somebody who sets out to be a commercial songwriter, whose goal is to have hits and make money—I mean, I don’t understand that mindset, and I’ve never subscribed to it—okay, it’s fine. If that’s what they want to do, more power to them. They should go do that. We should just treat each other in a friendly and respectful manner and leave it at that.

If that concern comes back, it’ll be because the artists are sickened that everything is about money. There is a strong strain in the human spirit and psyche that wants something bigger and of greater value than money. Those kinds of feelings get expressed in the arts more readily than anywhere else. I suspect there will be a pendulum swing at some point away from the intense materialism we are bombarded with right now. It may come from the economic bottom who are getting screwed anyway.

Credits:

M.D. Dunn is a musician, writer, and educator from Northern Ontario, Canada. Find him online at www.mddunn.com

This interview first appeared in The Rumpus

January 18, 2018 – interview date